Mimi Sheller Essay: Navigating AR2View

Navigating AR2View

Mimi Sheller

Professor of Sociology

Director, Center for Mobilities Research and Policy

Department of Culture and Communication

Drexel University

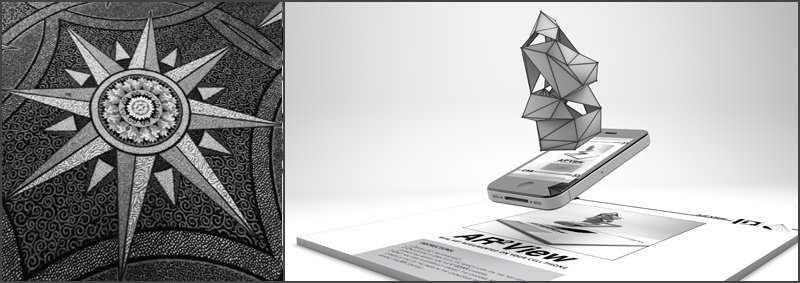

Many people are becoming aware of Augmented Reality (AR) through its increasing use in commercial applications on smartphones (used for everything from finding subway stops and pop-up wiki-info, star gazing and shooting aliens, to shopping in the IKEA catalog). Yet few know that mobile locative artists have been at the forefront authoring more playful and challenging AR experiences to populate this frontier of spatial and visual experimentation. This AR2View catalog invites you to the locations where artists have transformed specific physical locations with a “mixed reality” experience.

Mobile locative art includes a diverse set of practices that are not simply about screening digital art on portable devices, but might involve sound walks, psychogeographic drifts, site-specific story-telling, public annotation, digital grafitti,

collaborative cartography, or ever more playful “digital cityscapes.”1 Even wandering through the generic hallways of a conference hotel can be transformed with the interruptions of digital imaginaries into the non-places of the conference circuit. Mobile locative artworks tend to engage the corporeal body, the physical location, and the media

interface through a complex mixture of sensory and kinaesthetic experience, navigational and locative choreographies, and social relations that may extend across many scales, but might just involve riding an escalator or opening a door handle.

In my series of recent collaborations with artist Hana Iverson,2 we suggest that locative mobile media art is one of the key arenas in which emergent interactions with sensory dimensions of place, temporality and presence itself are being explored. AR combines virtual data with physical locations, generating an immersive and interactive real-time

environment, with the potential for producing new experiences of “augmented” urban space and “net-locality”, even (or especially) in a hotel lobby.3 Unlike commercial applications, artists often draw on more disruptive and critical traditions that seek to defamiliarize the familiar, to heighten our sensual awareness of location, or to offer new forms of place-making and public engagement.

The Virtual Public Art Project (VPAP), including artists showing their work here, has been creating AR sculptures for several years now. These pieces are public displays of three-dimensional digital works creating “a view of the physical real-world environment merged with virtual computer-generated imagery in real-time.” They transport us elsewhere by transposing objects in space. The smartphone interface can make the experience of these artworks immediately intuitive and comfortable, even as it modulates otherwise unremarkable spaces in novel and often subtle ways.

Members of the group ManifestAR, also included here, have been inserting digital objects and Flash animations into highly political public locations for some time: from locations of death on the US-Mexico border, to the Goddess of Liberty in Tiananmen Square in China and across the protest sites of the Arab Spring. Their work also “hacks” institutional spaces, including oil gushing from the BP logo following its massive spill in the Gulf of Mexico, to digital artworks placed in the inner sanctums of the Museum of Modern Art or within the CAA conference location itself.

The physical and the virtual overlay each other, superimposing bodies and data, digital and material presences, into a hybrid assemblage. In such “transarchitectures,”4 mobile AR remediates our existing habits of viewing, navigating and sensing place, both scattering and intensifying the here and now. Now “you can leave your mark on the world or read the marks others leave behind, re-creating place in a Borgesian digital map. Artifacts and places will be imbued with memories in a far richer way than ever before.”5

As Lauren Cornell, of the New Museum, and Brian Droitcour wrote in their recent response to Claire Bishop’s piece on the “Digital Divide” in the 50th Anniversary Issue of Artforum (which seemed to question the relevance of digital art), “Digital art is no longer confined to ‘cyberspace’. Concerns about networked technologies have been absorbed by artists who draw on their knowledge of painting, sculpture, performance, and installation, as well as an interest in

computers and code.”6 Bishop responded that artwork in the “new media niche” misses the point if it is “fixating on the centrality of digital technology rather than confronting it as a repertoire of practices and effects that increasingly lodges capitalism within the body.” Here, then, we invite art audiences, producers and critics to enter the debate: let these AR works lodge in your own body, and consider their potential effects for yourself.

___________________________

1De Souza e Silva, A. and Sutko, D. M. (Eds.) (2009) Digital Cityscapes: Merging Digital and Urban Playspaces, 251-268 (New York: Peter Lang).

2This includes a double session on Mobile Art: The Aesthetics of Mobile Network Culture in Place Making at the 2012 College Arts Association conference, a co-curated exhibition called LA Re.Play (http://www.lareplay.net/), and a special issue of Leonardo Electronic Almanac (Sheller, Iverson, Aceti, and Hight, forthcoming).

3Gordon, E. and de Souza e Silva, A. (2011) Net Locality: Why location matters in a networked world, Boston: Blackwell Publishers.

4Novak, M. (1997), “Transmitting Architecture: The Transphysical City”, in A. and M. Kroker (eds) Digital Delirium (St. Martin’s Press, New York), pp. 269-70.

5Varnelis, K. and Friedberg, A. (2006), “Place: Networked Place”, Networked Publics (Cambridge: MIT Press), http://networkedpublics.org/book/place.

6Lauren Cornell and Brian Droitcour, “Technical Difficulties”, Artforum, Vol. 51, No. 5 (January 2013), p. 36, letter in response to Claire Bishop,

“Digital Divide”, Artforum, Vol. 51, No. 1 (September 2012), pp. 435-41.