Expose: IN 2070 & New Heroes

IN 2070 & New Heroes

Annette Barbier, 2012

http://iam.colum.edu/abarbier/Expose/EIO.html

Project Statement

IN 2070

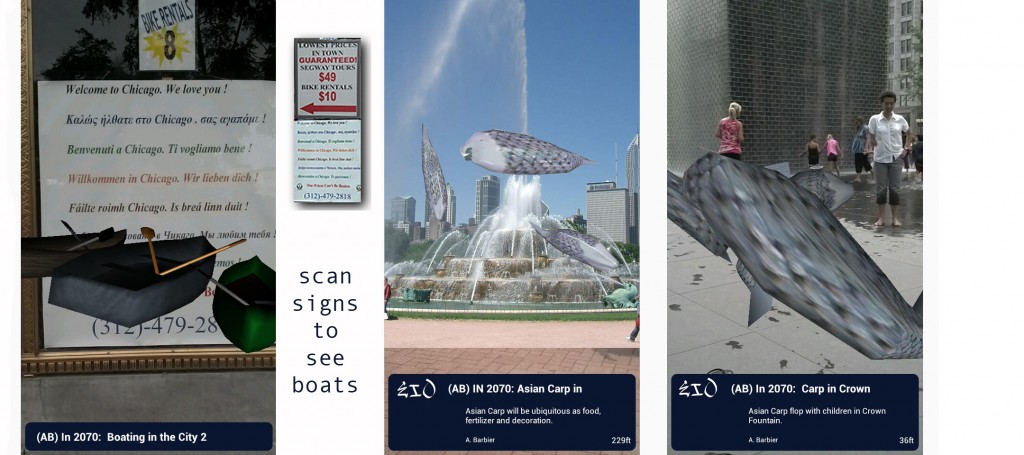

The title of the work references an article in the New York Times from May of 2011 that describes Chicago’s efforts to adapt to climate change. Chicago is expecting alternating periods of flood and drought, while battling invasive species such as the Asian Carp that threaten to destroy native ecosystems. This work looks forward, in somewhat fanciful terms, to making the best of the situation, from using canoes rather than segways for tourist rentals to embracing carp as ubiquitous decorative companions.

Boating in the City: 310 S. Michigan, 2 reference images; Climate change is characterized by periods of drought and flood, so in 2070, canoes may replace bicycles as transportation.

Asian Carp in Buckingham Fountain: Buckingham Fountain; Asian Carp will be ubiquitous as food, fertilizer and decoration.

Asian Carp in Crown Fountain: Crown Fountain, Michigan Ave. and Monroe St.; Asian Carp flop with children in Crown Fountain.

Daley Plaza Fountain, Daley Plaza, NE corner, Clark and Washington; Imagining Daley Plaza fountain with frolicking Asian carp.

New Heroes:

The history of North America did not begin with its European immigrants, although our history books often assume that it did. When Europeans arrived, estimates* place the then current population of N. America at between 8 and 18 million. Within a few years after initial encounters with Europeans, native populations were decimated, with an average depopulation rate of 95%, prompting some to characterize our joint history as an American Holocaust. White governments and settlers relentlessly deceived, badgered, stole from and ultimately killed native populations, forcing many on long treks into inhospitable territories and climates. We have begun to honor native leaders who fought in their various ways for the rights of their people. This work acknowledges their bravery and persistence by renaming streets from Washington to Harrison with the names of native leaders, and in one case, by returning the weapons we took from them.

American Holocaust, David E Stannard, 1992, Oxford University Press

Black Hawk (1767 – October 3, 1838) Washington St. & Michigan Ave.

Led the Sauk people to ally with the British against US incursions on native lands, in particular in response to an 1804 treaty in which all Sauk land E of the Mississippi was ceded to the US without proper representation from the tribal council. In his surrender speech of 1832, he said, speaking of himself: “He has done nothing for which an Indian ought to be ashamed. He has fought for his countrymen, the squaws and papooses, against white men, who came year after year to cheat them and take away their lands….The white men do not scalp the head; but they do worse, they poison the heart – Farewell, my nation!”

Tecumseh (March 1768 – October 5, 1813) Madison St. & Michigan Ave.

Tecumseh was a Native American leader of the Shawnee and a large tribal confederacy which opposed the United States during Tecumseh’s War and the War of 1812. Younger braves especially admired him, because of his call for violent resistance against further white settlement of native land. Tecumseh has become an icon and heroic figure in American Indian and Canadian history.

Sacajawea (c. 1788 – December 20, 1812) Monroe St. & Michigan Ave.

A member of the Agaidika tribe in Idaho’s Lemhi Valley, born near what is now the town of Salmon, in about 1788. She was abducted and enslaved by the Hidatsa tribe at the age of 12, and forced to marry Toussaint Charbonneau, 3 times her age, at the age of 16. She is well known as a member of the Lewis and Clarke expedition, whose purpose was to discover an overland route to the Pacific. She traveled, by boat and on foot, for hundreds of miles, on a journey that began 8 weeks after the birth of her first child.

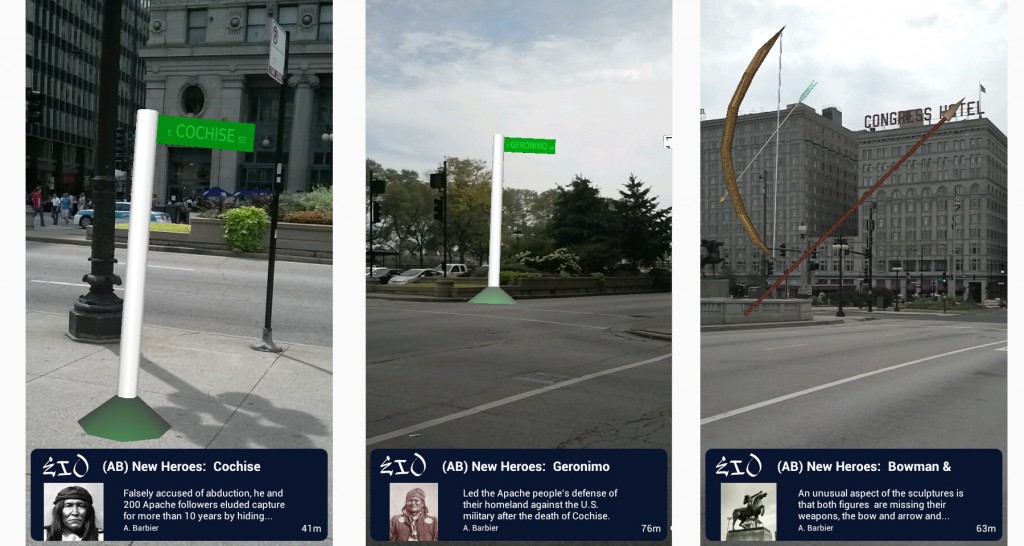

Cochise (c. 1805 – June 8, 1874) Adams St. & Michigan Ave.

After working for several years as a woodcutter for a stagecoach line, he was falsely accused of and punished for abducting a white child. There followed a series of retaliations and persecutions by white troops, and he and 200 Apache followers eluded capture for more than 10 years by hiding out in the mountains of Arizona. He eventually surrendered and lived the remainder of his life on the Chiricahua Reservation where he died on June 8, 1874.

Geronimo (June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) Jackson Blvd. & Michigan Ave.

Led the Apache people’s defense of their homeland against the U.S. military after the death of Cochise. In 1874, some 4,000 Apaches were forcibly moved by U.S. authorities to a barren wasteland in east-central Arizona. Deprived of traditional tribal rights, short on rations and homesick, they revolted. Spurred by Geronimo, hundreds of Apaches left the reservation to resume their war against the whites. He and a small band eluded capture for 5 months, while pursued by 5,000 white soldiers. After his eventual capture, he was promised that he and his followers could return to Arizona after a period of exile in Florida, but he never saw his homeland again.

Crazy Horse (c. 1840 – September 5, 1877) Van Buren St. & Michigan Ave.

War leader of the Oglala Lakota. He took up arms against the U.S. Federal government to fight against encroachments on the territories and way of life of the Lakota people. When the War Department ordered all Lakota bands onto reservations in 1876, Crazy Horse became a leader of the resistance. He gathered a force of 1,200 Oglala and Cheyenne at his village and turned back General George Crook on June 17, 1876, as Crook tried to advance up Rosebud Creek toward Sitting Bull’s encampment on the Little Bighorn. After this victory, Crazy Horse joined forces with Sitting Bull and on June 25 led his band in the counterattack that destroyed Custer’s Seventh Cavalry. He was bayoneted in the back while taking his sick wife to her parents.

Sitting Bull(c. 1831 – December 15, 1890) Harrison St. & Michigan Ave.

A Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux holy man who led his people as a tribal chief during years of resistance to United States government policies. He won a major victory at the Battle of the Little Bighorn against Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry on June 25, 1876. After working for 4 months in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, he said: “[I] would rather die an Indian than live a white man.” He is praised as one of 13 great Americans by President Barack Obama in his children’s book “Of Thee I Sing: A Letter to My Daughters.”

Chief Alice Brown Davis (September 10, 1852 – June 21, 1935) Balbo & Michigan Ave.

A leader of the Seminole people, she worked diligently to help her people adapt to white culture while retaining their Indian heritage. In addition to teaching and working to maintain tribal control of education, she was a tenacious fighter for land rights of the Seminole Nation.

The Bowman and the Spearman, Congress Plaza Gardens, S. Michigan Ave. (100 E) & E. Congress Pkwy. (500 S)

Sculptor: Ivan Mestrovic, 1928; Bronze figures, H 17 ft. (each)

Commissioned by the B.F. Ferguson Monument Fund, to commemorate Native Americans.

The warriors were left weaponless so that their exact construction could be imagined by the viewer, and it seems ironically appropriate that this lack implies that the Indians are powerless to overcome the forces of white “civilization” that ultimately destroyed them as a nation. This work restores to them their weapons.

Biography

Annette Barbier uses new technologies to address issues of home, defined locally as domesticity and broadly as the ways in which we relate to our environment. Her work has moved from an emphasis on the personal to a consideration of the global, looking at ways in which home has come to be re-defined as populations shift, as our interdependence becomes increasingly clear, and as the natural world deteriorates.

Barbier received an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work has received national recognition in venues including Image Union, broadcast on WTTW Chicago, the Chicago International Film Festival, Dallas Video Festival, Women in the Director’s Chair, Houston Film Festival, The Learning Channel, San Paolo Video Festival, as well as new media festivals and conferences such as IDMAA (best of show 2005, featured artist 2011), ISEA, and Ars Electronica.

Her most recent work uses computer-controlled laser cutting and engraving on natural materials such as leaves and feathers to heighten our awareness of our detrimental impact on the natural world, and is using augmented reality to create works for urban environments that ask us to both remember what we have lost and to imagine what the future will bring in a series that uses mobile devices to display images and models of the natural world as it was and as it will become if climate change continues unabated.

Barbier created and directed the Center for Art and Technology (1999 – 2005) at Northwestern University where she taught from 1982 – 2005. She is now a professor in the Interactive Arts and Media Department at Columbia College, Chicago, where she teaches new media theory and practice.

More detail at: http://iam.colum.edu/abarbier